Cava is one of Spain's most infamous wines - this sparkling wine finds itself sandwiched in between the cheaper, less exciting offerings on a wine list or shop shelf. Most serious Champagne drinkers steer themselves well clear of it.

I never understood that despite everything I read on paper about Cava (that is must go through the same expensive production method as Champagne to give it a natural bubble as opposed to the quickly produced carbonated bubble of Prosecco), it was cheap and quite frankly unpleasant.

I started to look into the ‘Why’s of it. Why did what I was tasting seem so far away from a quality wine? Why was some much money and time being spent on a wine that was made in such a way for the end the end result to be lackluster and drab?

Whilst the majority of Cava is produced in and around Penedes, near to Barcelona – the legal requirements for a wine to be called Cava is that it is can be produced anywhere in Spain providing it is made with the traditional method and has been aged appropriately.

I drew my focus to Penedes and what happens there in the heart of Cava production.

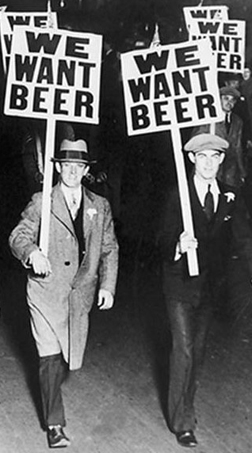

Each year around 260 million bottles are produced and approximately 80% of this is made by two producers. There are around 250 producers of Cava with less than 10 of these producing cava from their own vineyards.

On those facts alone it starts to become very clear as to why the quality falters. Alongside this, the Cava DO is very relaxed in comparison to the legal requirements in place in other sparkling wine regions such as Champagne.

As mentioned earlier, legally Cava can be made from many regions all over the country. The producers are legally allowed to produce Cava from up to 9 different grapes and due to hot climate in some of Spains regions – it is legal for producer to acidify their wines too. It is also commonplace that the majority of the producers buy their grapes and base wines from other growers.

As my research progressed, the facts revealed the truth in what I had been tasting but with every region and appellation this is always more than what is seen on the surface and Cava is no exception. It is a small movement here, there are around a dozen producers that revert from the norm and produce wines with care from their own vineyards.

And with relief I was lucky enough to discover the Recaredo wines.

Recaredo is a 3rd generation estate with 50ha of vines. The estate was founded in 1924 and is now in the hands of Ton Mata. Ton converted all the vineyards to Biodynamic several years ago and has never looked back.

Ton is a curious man who seeks to produce a high quality cared for wine, he has extended his research further afield – Recaredo are working alongside the Foods Technology Department of the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. This research project is on yeast – Recaredo are selecting yeasts from their own vines and then experimenting with to see how this affects he personality of their wines.

The ethos at this estate is for all their wines to express grape, place and vintage. Recaredo try to work majorly with Xarelo - for it's ageing potential aswell as its capability of expressing where it is grown.

All wines are Non Dose and vintage, with longer ageing that they are legally required. It is worth mentioning that there is no acidification here. The long ageing of all their wines (with some of their wines ageing for over 100 months) before their release, these deliver something quite special, with high levels of complexity that has been derived from the long time on lees. Recaredos’ Gran Reserva is aged for 50 months when the DO only requires 30 months. All the wines are hand riddled and hand disgorged.